Ronald Andrew Wilford, November 4, 1927-June 13, 2015 |

Ronald Wilford was born in Salt Lake City on November 4, 1927, the second of seven children of a Mormon mother, the former Marcile Gerstner, and a Greek Orthodox émigré who left the old country as Andreas Bouloukos. He learned discipline and responsibility at an early age. Trudging along with his father and his big brother Wayland on late-night janitorial shifts robbed young Ronald of untold hours of much-needed sleep.

But though he would later sum up his childhood as "miserable," Wilford valued the habit of hard work and always respected the hard work of others.

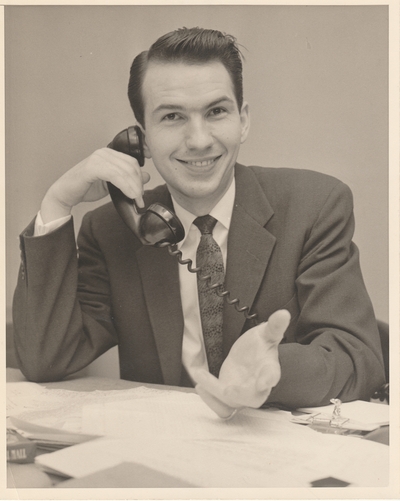

The world knew him best as the Silver Fox, for over a half-century the mastermind of Columbia Artists Management, Inc., which in his hands burgeoned into the farthest-reaching, most powerful, and most star-studded empire the classical-music business had ever seen. Who today remembers the Black Knight, as some called him in the early 1950s, newly arrived in Manhattan, teaching himself the ropes even as he was rewriting the rules?

Barely out of his teens, with the backing of a silent partner, he hung out his shingle as Ronald A. Wilford Associates. His one-man shop serviced a short but sterling roster that included the pioneering early-music ensemble New York Pro Musica; the rising pianist Byron Janis; and a handful of opera singers—Cornell MacNeil, Donald Gramm, Régine Crespin, Nicolai Gedda—whose reputations shine bright to this day. Fine work, if insufficient to satisfy Wilford's passion for adventure.

"The Black Knight" Ronald Wilford, fresh from Salt Lake City, out to conquer New York and then the world. |

Marceau opened on a Tuesday, supposedly for a limited run of two weeks. The early editions on Wednesday ran notices that were ecstatic if also somewhat incredulous;

Brooks Atkinson concluded his rave with the one-sentence paragraph, "Only a fortnight, the man says." Lines formed around the block. Wilford celebrated by heading over to the box office and withdrawing some cash to buy his first good suit. At the same time, he scheduled his first-ever appointment with a dentist.

Fast-forward four decades, and there is Wilford, colonizing the East Village once again. The property this time is Stomp, the musical with no music and no dialogue, set in some junk-strewn corner of the urban jungle, pulsing with the sounds of bodies in collision with inanimate objects. A CAMI manager had brought Stomp over from the Edinburgh Fringe Festival for a modest tour that generated lots of buzz. Though Wilford had not yet seen the show, his ear was to the ground, and he booked it into the 277-seat Orpheum, where two decades plus and some half dozen road companies later, the beat goes on. In a different, faraway part of the pop galaxy, Wilford orchestrated the transfer of Howard Shore's Lord of the Rings soundtracks to the concert hall, both in the form of screenings to live accompaniment and of a freestanding six-movement symphony that has toured the world.

Ronald Andrew Wilford: an American original, whose Horatio Alger biography has yet to be written—not that he would have endorsed the project.

"I'm not important"

In striking contrast to current generations, Wilford never conceived of himself as the star of his personal reality show. In family snapshots, you will find him beaming on the sidelines or hiding his face behind a dinner napkin, helpless with laughter. Formal portraits scarcely exist; even candid shots are rare. The photo archives from his years at CAMI amount to little more than a half-empty shoebox, stocked with a few treasures, but only a few. One such shows him in the company of a troika of his conductors: Eugene Ormandy (born 1899), Seiji Ozawa (born 1935), and James Levine (born 1943), no trace of rivalry evident among them. A priceless addition to the image bank, received from overseas just weeks ago, shows Wilford with Ozawa and Mstislav Rostropovich, titan among cellists, on "caravan" in remotest Japan, dropping in without fanfare, a documentary crew, or the shadow of mercenary intent, bearing gifts of choicest Haydn and Boccherini to whoever happened to be there to hear.

Ronald with three generations of Men In Black Tie. From left: James Levine, Eugene Ormandy, and Seiji Ozawa. |

Over a marathon six-decade career, Wilford proved as resourceful serving clients who were one of a kind, like Marceau or the reclusive keyboard genius Glenn Gould, as he was managing a virtual monopoly on classical conductors, competitors though they might be. "Ronald Wilford: Muscle Man Behind the Maestros," a profile by Stephen Rubin published in the New York Times on July 25, 1971, gave readers beyond the music industry a rare glimpse into the inner sanctum.

"The ego behind the ego of Herbert von Karajan, Seiji Ozawa, Eugene Ormandy, Rafael Kubelik, Thomas Schippers, Andre Kostelanetz and 70 other conductors, is a manager who is more widely feared, envied and disliked than any of his superstar maestros," the story began. Wilford's artists were likened to "pawns" in his "chess game," said to be "considered by some the most expertly and by others the most ruthlessly played in the business." According to unnamed industry sources, Wilford could be "brusque to the point of rudeness," which supposedly amounted to a "fatal flaw," which in turn suggested some unspecified Aeschylean tragedy on the horizon.

"My artists don't think I am a sonofabitch," was Wilford's defense, "and I don't care what anyone else thinks."

"I don't care!" That was a mantra of Wilford's. Twisting the quote against him was child's play. For a less equivocal expression of what he was getting at, consider a recent remembrance of James Levine's: "Some people try to put on and take off their integrity like a suit of clothes, at their convenience. With Ronald, there was none of that."

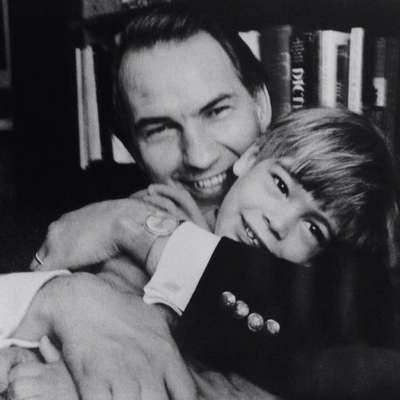

Wilford with his son Chris, who always came first. |

Wilford, recovering workaholic, deep in the heart of the piece. "Now Christopher always comes first ... And there isn't one conductor I manage who wouldn't understand."

At this remove, Rubin's cross-examination—hard-boiled veneer notwithstanding—reads as a scrupulously shaded account of his notionally hostile witness. Point of fact: after radio silence that lasted decades, the two men were to become close friends. But what Wilford felt at the time was naked betrayal. Once burned, he never let the press near him again.

Well, hardly ever. Norman Lebrecht, Edward Gibbon to the classical-music industry, penetrated Wilford's defenses in 1988 while researching his Decline and Fall, published as The Maestro Myth: Great Conductors in Pursuit if Power. By default, a dozen-plus breathless pages under the chapter heading "The Master of Them All?" have gained acceptance as the standard text on Wilford, never mind arguable excursions into pulp fiction. Did Wilford ever stoop to set the record straight? Certainly not. He didn't care. To do so was not important.

Among friends

This writer's personal history with Wilford was brief. I suppose he must have known my byline from the New York Times, where my freelance stories on music and dance began appearing in 1985; when I bumped into him on a bus en route to the Bayreuth Festival, the conversation began and ended with introductions. But then, in October or November 2009, my phone rang and there he was, wishing to consult me on a personal matter. Reminding me how publicity-shy he had always been, he told me his wife was after him to make sure that when the bell tolled, a proper account of his life and achievements appear in the Times. Would I accept his assignment to write such a text?

I answered that any attempt on the part of a non-staffer to plant a file in the Times morgue could only backfire, assuring him that such a file must exist already. As it later proved, that wasn't so: Wilford's lifelong determination to fly under the radar of reportorial scrutiny had succeeded only too well. Happily, when the time came, better-connected intercessors came into play, resulting in an obituary by Michael Cooper that was comprehensive, accurate, and respectful.

But all that lay in the future. Ronald, as he then instructed me to call him, thanked me and asked me to send my invoice. When I said I could make no charge for five minutes off the cuff, he invited me to lunch at his regular corner table at Marea, on Central Park South.

After sharing menu tips, Ronald talked shop for a while. In particular, he recalled the glory days of Community Concerts, when CAMI artists performed on subscription series all across the United States, building local constituencies in hundreds of cities, large and small. He criticized recent efforts to adapt the old model to our new landscape of social media and Live in HD as amateurish, tardy, and distracted. He foresaw great potential for the Community Concerts concept in China, where the talent pool is inexhaustible and underserved audiences run to hundreds of millions. "So that's what it means," I thought to myself, "to be a master of the universe."

And then, out of the blue, Ronald opened another door. What did I think, he asked, of Luc Bondy's widely reviled new Tosca at the Metropolitan Opera? A run-of-the-mill staging, I thought, punctuated with a few modish obscenities, the whole delivered in a very ugly box. But the end of the second act, singled out by many purists for particular scorn, had struck a chord with me. The villain, as you'll remember, lies dead at that point, stabbed by the heroine under extreme duress. The playbook then calls for her to place a crucifix on the corpse, set a candlestick by his side, and steal silently away to the sound of her rustling cape and the whoosh of the falling curtain. Under Bondy's direction, Karita Mattila sank onto the sofa, ashen, contemplating (as it seemed to me) the wreckage of her life on what was meant to be a starlit night of love.

Ronald listened, and then he spoke. "Let me tell you what's wrong with the production," he began, elaborating in rigorous detail, alive to the composer's and librettists' every nuance. He spoke with particular sensitivity of the gloom and the stillness and the romance of the opening of the third act—of Cavaradossi's reflections while awaiting execution, of the magical transition from darkness to the glimmerings of first light.

To listen to Ronald just then was to fall under Puccini's familiar spell as if for the first time and more deeply.

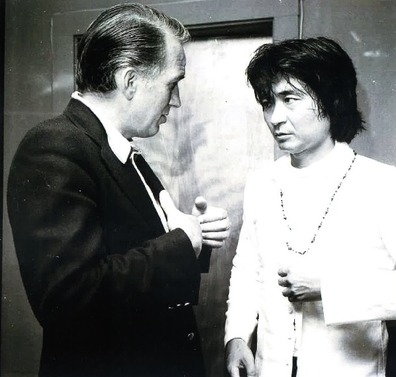

With Seiji Ozawa, whose career Wilford guided from the first. |

"He cried," Ozawa answered. 'Always he cried."

And crying was a good thing?

"I think it was," Ozawa says.

Ronald on Ronald

After Marea, I hoped there would be many chances to continue the dialogue with Ronald, or for me just to learn and listen. That didn't happen, though a generous check for my "consultation" arrived a few days later by mail. But off and on during his remaining years and much more since his death, Ronald's artists, colleagues, and immediate family have shared with me reminiscences of his friendship, vision, generosity, loyalty, and love—no one more richly than Christopher, who always came first, and Sara Wilford, his wife of forty-three years, whom his staff knew always to put through when she called, no matter what.

The lion's share of the impressions stitched together here come from them. But as luck would have it, we also have an impromptu self-portrait Ronald set down in 2013, when a law-graduate nephew he seemed not even to have known reached out in a dark mood, hoping to discover how Ronald had managed to fly the coop and touch the sky. The young man, whose name has been changed below, signed his e-mail, "Eager, capable, and bored."

Ronald's answer combines, in seamless fashion, autobiography, reflection, candor, good humor, and good counsel.

Dear Nico,

I probably should address you as "Dear eager, capable, and bored." You did not mention your age. I assume you are around 24 or 25. I mention this because you seem to relate my story to the one you are living. Far from the truth. I found my "passion" early in my life, and it was confirmed at the University of Utah when I met a man named Gail Plummer who was in the Speech department and had a very small class on Theatre Management. He was the one responsible for building the U of U Theatre productions and selling subscriptions to these events. They were terrific, and I became completely immersed in the promotion of these productions and in their execution on stage. He introduced me to a Utah pianist, Grant Johannesen, who had a young manager in New York City. I agreed to work for him in the West and became a partner of his Manager in the West. I left the U of U because I knew that I wanted to give all of my efforts to this endeavor—the performing arts. It was agreed that rather than continue an office in Salt Lake City, I would move to New York City and work from there.

I stayed with this New York management for two years and then went into business for myself—I was 25 years old. It was not to leave a life or because I was bored. I was having a lot of fun in the theatre and in promotion, and I loved all aspects of it, even though I was completely broke living in a "cold-water" room in NYC. My earliest exposure to theatre was when I helped my father clean the Orpheum Theatre in SLC—I was probably 8 years old. I must also say I was always anxious to leave SLC, because the culture did not fit with my psychological make-up.

So, we should speak about you. I cannot tell you how to find something which causes you to forget yourself—I believe Freud said, "The loss of self is the basis of creativity." So that is the process of how I constructed my life—all of my activities—my failures and successes (not really important)—because I had and am having a fabulous life and enjoy many extraordinary relationships in my activities and with my wife and family.

I do have much empathy for your position. Many people do not have my good fortune of knowing their passion at an early age. I cannot know what interests you or "what turns you on." If nothing does, then you have a problem which only you can solve. You have the education, knowledge, and some experience which could enable you to execute anything you wished to do. A law degree is a fabulous foundation for any endeavor. Why don't you just think about what makes you smile and forget yourself through your interest in this other thing? Being bored is not the answer—in fact, you should never be bored—the world is too interesting and what man has done and created is really fantastic and should turn you on.

Have fun!

As far as a layman can determine, the comment attributed to Freud is not verbatim. Nor is the frequently cited dictum, which I sense shining through Ronald's reflections, that the foundation of a happy life consists of work and love. But scholarly scruple is not really at issue here. Beyond question, Ronald had taken very much to heart Freud's writings (which he kept at his elbow and frequently dipped into), and, more to the point, Freud's discipline of self-inquiry. In truth, Ronald must have discovered his disposition for such work early on and begun the practice on his own. Following Sara's example at a moment of crisis during her first marriage, he entered classical psychoanalysis, initiating an exploration that continued the rest of his life.

Ronald and Sara at the foot of the Acropolis, in Athens. |

And in Ronald's case, thoroughly grounded in the here and now; that signoff of his—"Have fun!"—is revealing. He made a point with Sara's children from her first marriage that they had a father, and it wasn't him, but how much closer could they really have been? "Up in the country, he loved to garden," Sara says. "He would get my kids into the soil. 'Get into the soil,' he'd tell them. 'Plant those bulbs! You'll see what comes up in the spring.'"

Come vacation, on the Greek island of Mykonos, Ronald spent hours building sand castles with Sara and their youngest children. While recruiting Russian attractions, he introduced two teenagers to Moscow and Tbilisi. With a stepson fresh out of high school, his backpack packed for Asia, Ronald shared an intense all-nighter of cognac and counsel. Other stepchildren he took galloping across the sands of the Sahara or pedaling among legions of locals through the epic congestion of Beijing. More than once, Ronald took Sara's tomboy daughter shopping for clothes she screamed she would never wear. "I don't care!", he yelled back, and bought them anyway. And when Chris, the boy who was his son, turned thirteen, Ronald granted his wish, soldiered down in suit and tie to see Kiss at Madison Square Garden, smiling throughout the show. "How did you like it?," Chris asked afterwards. "It was great!," Ronald answered.

Never be bored, he said. Daisy Ramos, the beloved housekeeper of his final years, vividly recalls his last morning, Saturday, June 13, 2015, when he woke up at home on Fifth

Avenue, overlooking the reservoir in Central Park. As Sara fixed breakfast, Ronald turned to Daisy, gave her a bright smile, and asked in that expectant way of his, "What are we going to do today?"

Postscript: After Ronald's death, Nico wrote to Sara with an update. Galvanized by Ronald's encouragement, he had carved out a niche in real-estate development, a field that challenges and inspires him. Ronald had an instinct for such interventions, in private life and in his work.

A teacher in spite if himself

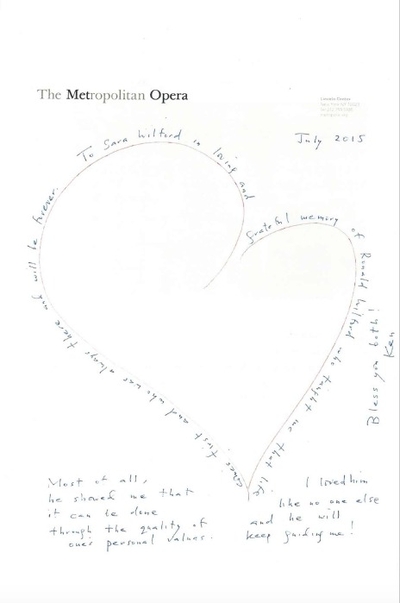

Condolences from Ken Noda, ex client but a friend for life. |

And there was a letter from a former artists manager at CAMI, now a sister in Bethlehem, Connecticut, who had asked Ronald to stand by her on the solemn day when she entered the religious life of cloistered poverty.

He delivered her from church to the Great Gate of the Abbey of Regina Laudis in the glamour of a classic Jaguar; soon, they would look back on that ride in the light of a father walking his daughter down the aisle. Two years later, he returned for her reception of the habit, and witnessed the intimate ritual of the cutting of her hair.

It was Ronald's nature to face a sphinx when one crossed his path, and he motivated others to do the same. The Socratic process might begin with a simple, game-changing question, typically no more than, "Why?" In political debates, he avoided frontal attack in favor of deft query under which opposition, as often as not, would eventually self-destruct. As Chris was growing up, Ronald stood by principles ("I can't do that") but did not impose them ("I can't stop you"). But make no mistake; he could also be tough, as Sara can tell you.

"I came to teaching because of Ronald's infuriating challenges," Sara said at the family service for Ronald in Stockbridge, looking back on three decades as director of the Early Childhood Center and the Art of Teaching graduate program at Sarah Lawrence College, from which she retired only this June. When she and Ronald first met, he was managing her first husband, the pianist Anthony di Bonaventura.

"What are you going to do with your life?" Ronald demanded.

"A dinner guest," Sara continued the story, "he had just said goodnight to my five kids. I was preparing food with one hand in my tiny kitchen and swigging a strong gin and tonic, fixed by him, in the other. I was livid! ('Didn't you just say goodnight to a band of very young children?')"

"'No", he shot back. 'What are you going to do for you?' I didn't throw the drink at him. Instead I ended up in Continuing Education, which led to a BA and Teacher Certification, public school teaching, graduate degrees, writing, and a career at Sarah Lawrence College. (And we married—but that's the love story.)"

Born into American aristocracy, Sara says that for the first half of her life she tried to escape the image of being someone's granddaughter—that someone being U.S.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt. As Sara Wilford she finally found an identity of her own. "Ronald gave me that," she says. As the distinguished educator she was, she saw the teacher in him. "I'm no teacher," Ronald demurred, perhaps picturing classrooms and textbooks and chalkboards.

Yet teach he did, both by precept and example. His managers at CAMI got the (figurative) memo not to show up for sales calls with folders and papers, because it made them look like salesmen. Likewise they also knew never to lose their temper in negotiations, except for calculated theatrical effect. These were just two of Ronald's Ten Commandments, as compiled by a CAMI executive for some festive occasion; unfortunately, the document has been lost.

Conceptually, Ronald drew a sharp distinction between booking agents, who simply wrote and kept track of a client's contracts, and artists managers in the full sense of the word, who approached their job strategically.

Matthew Epstein, a brash, very young manager just fired from the boutique of an accomplished salesman (the prim and proper Harold Shaw), received a warm welcome from Ronald for his well-honed sales skills, his comprehensive knowledge of opera, and his bagful of fresh ideas. Severe as Ronald could be, it never bothered him (more likely it gave him a bang) that Epstein gave as good as he got. The whole point of recruiting new managerial talent was to diversify the portfolio. That said, Ronald made it his business to give Epstein a crash course in strategy.

"First of all, an artist had to function well," Epstein says. "Ronald used that word function all the time. That was the artist's job: to function efficiently, very well, which meant knowing how to behave with the conductor, with the stage manager, and crucially the management team. When they got invited to a post performance party, they had to understand the professional importance of their interactions there. Basically, artists who function well are invited back without pressure from the managers. Preparing them to understand and accomplish that was one important aspect of the Wilford strategy. You also had to find them the right kinds of diverse exposure. If an artist was booked for a preponderance of orchestral and recital engagements, the manager had to make sure to balance those with high-level operatic engagements, and vice versa. Exposure in key markets in Europe, Asia, and South America was also crucial. Ronald was enormously helpful in teaching me how to develop an artist's worldwide career and reputation."

Peter Gelb, general manager of the Metropolitan Opera and a CAMI alumnus, today attracts much of the wariness, not to say antagonism, the media used to harbor for Ronald—as those in positions of perceived power often do. In the naive imagination, power; while it lasts, denotes the capacity to inflict one's bad choices on unwilling pawns. If only it were so simple.

"Ronald was a visionary." Gelb says, evoking his Socratic personality from yet one more perspective. "He saw the manager's role as creating a safe haven for artists, helping them to be who they were, to achieve what they wanted to achieve. He had an extraordinary ability to compartmentalize. Often, he would be working with artists who were in competition with one another. But they trusted him and wanted to work with him. Artists accepted his integrity. People believed what he said. He wasn't a bluffer. He was true to his word. I'd like to think he instilled that value in me. I do what I say. That's the only way I can work. I learned that from Ronald."

The personal touch

Diplomatic and artistic coup: a homecoming to the USSR for Rostropovich, leading the Washington National Symphony. |

With high-strung, high-maintenance thoroughbreds, Ronald likewise had a horse-whisperer's flair. For the imperious Karajan, to whom the backstage scrum after performances was unendurable, Ronald had a limousine waiting at the stage door to whisk him back to his hotel, a scalding bath, and a snort of iced vodka before the audience had even cleared the hall. (On request, Ronald arranged the same exit strategy for other maestros, who discovered that they did not like it.) When the skittish Carlos Kleiber suspected a personal profit motive on Ronald's part behind an offer from the Metropolitan Opera, Ronald waived his fee to secure the contract.

And then there was the piano virtuoso Vladimir Horowitz, last of his charismatic generation, who came to Ronald late in life, bored with old-fashioned concert routine, bored with retirement, but saddled with eccentricities that rendered him effectively unemployable. With his signature dexterity, Ronald squared the circle of Horowitz's Byzantine contractual demands and turned him over to his latest CAMI recruit, Peter Gelb, who had ambitions in video. The series of international blockbuster events Gelb laid on for Horowitz had audiences in raptures and played well on the screen.

The greater the challenge, the sweeter the victory. In 1967, in the wake of the Six Day War, Ronald hatched the idea of a coast-to-coast United States tour for the Israel Philharmonic, all expenses assumed by CAMI, with proceeds to benefit the orchestra. Time was of the essence. Four weeks later, the tour began.

Things that matter

No one clicks with everyone. At CAMI, artists and managers came and went, each with a tale to tell, not always a happy one. But relationships that withered fade against the many that flourished, in many cases beyond the scope of any commercial purpose.

A lesser-known case study, very much in point: the pianist Ken Noda, who signed with Ronald at age sixteen, on track for what promised to be a storybook career. But at twenty-seven, Noda walked away to join the music staff of the Met, where he spends his days out of public earshot coaching singers on every rung of the ladder.

"I never thought of Mr. Wilford as my manager," says Noda, who is Nisei, born in America to Japanese parents. "I thought of him as my spirit guru." Not merely because Ronald curated Noda's calendar with fanatic care, refusing offers that were flattering but unsuitable and booking recitals in obscure towns to build his confidence before the big breaks. Not only because Ronald had sensed, and said, that Noda was receding into the music rather than sharing his soul. But because Ronald had stood by him through personal firestorms—identity issues, family conflicts.

"He knew things were happening with me," Noda says, "but he never pushed me against a wall. He always received me. My parents went to him when I came out, brokenhearted, and he brought them around. Before I quit concertizing, we talked about it for two or three years. And then he said we would just have to cancel whatever contracts I still had. He cried. And immediately after, he wrote me a hand-written note. 'I'm always here for you.'" In the years to come, Mr. Wilford never disappointed.

Equally remarkable, in its different way, is the story of Rudolf Bing, general manager of the Met from 1950 to 1972. As the unyielding defender of his artists' interests, Ronald inevitably locked horns with Bing on occasion, notably when he urged Marilyn Horne, then basking in the glow of her spectacular house debut as Adalgisa in Norma, to step back from a verbal agreement to sing Charlotte in Werther. But when Bing, by now in retirement, began to suffer from dementia, Ronald gave him an office and a title and saw to it that his medical needs were met until his dying day. That was not the only case of Ronald's quiet personal philanthropy.

Framed in a hall outside Ronald and Sara's Manhattan bedroom hangs a numinous text from Maximus of Tyre, whose Orations hark back to the school of Plato in Athens even as they anticipate the Neoplatonist mystics of the Renaissance. The passage concerns the human incapacity of seeing, naming, or apprehending the divine. Why, Maximus asks, should we pass judgment on others' intimations of the ineffable?

"Let men know what is divine," he concludes. "Let them know: that is all. If a Greek is stirred to the remembrance of God by the art of Pheidias, an Egyptian by paying worship to animals, another man by a river, another by fire, I have no anger for their divergences. Only let them know. Let them love. Let them remember."

Some people love a lifestyle. Ronald loved life.

"Why do people have to think about a life after this one?," he would ask. "This one is amazing."