1. Looking back: an introduction

I was a shepherd, I had a flock of sheep

But my mother sold them, sold them

Now there are no sheep left...

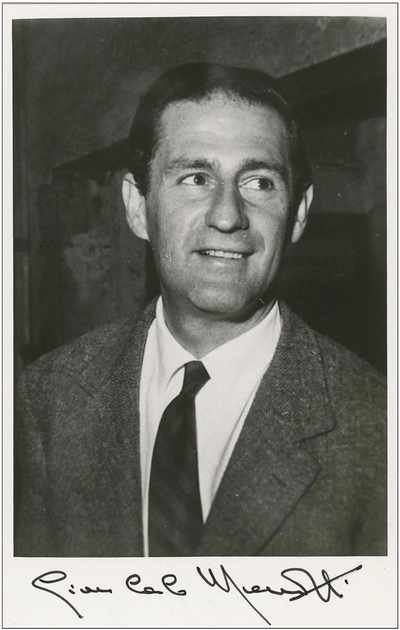

Four days shy of my fourth birthday, well past my bedtime, my parents plunked me down in front of the television set to watch Amahl and the Night Visitors, the inaugural presentation of the Hallmark Television Playhouse and a world premiere. That was on Christmas Eve, 1951. Tomorrow, Gian Carlo Menotti's shepherd boy turns 70. Yet in the popular imagination (not to mention my own), he hasn't aged a day.

It wasn't long before I had memorized the score virtually by osmosis, though over the years, Amahl's path and mine have crossed only occasionally. In 1960, when my family was living in Switzerland, we all trooped down to the opera house for our first Amahl in a theater. Sandra Warfield was appearing as Amahl's widowed mother, one night's sleep away from homelessness. In 1961, we went back to see Mary Davenport in the part. Both belonged to the company's resident ensemble, but Mary had seniority, and we had known her longer. Thus it was from Mary that I caught my first glimpses of veiled diva rivalry and drew my first conclusions about fan diplomacy.

The Adoration of the Magi, by Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1495), reputed to have inspired Menotti's opera. (Where's Amahl?) |

This year's anniversary seemed a proper occasion to share the Times story with a new generation of readers—along with my other Amahliana. From the website of Opera Depot, an excellent source for historic performances, I include the briefest of notes on the air check of the Italian premiere, with a Golden Age cast, Leopold Stokowski at the podium, and a huge, heart-breaking cut. The current post from Air Mail documents the opera's universal appeal as evidenced on YouTube. In closing, I append incidental thoughts that have found no place elsewhere.

*

2. A game Amahl marches triumphant (New York Times, December 5, 1999)

In the beginning. Chet Allen and Rosemary Kuhlmann as Amahl and his Mother in the original telecast of Menotti's Christmas special. |

At 88, Mr. Menotti, the Italian-born composer, director and librettist, claims to tire more easily than of old and apologizes for memory lapses, but his enjoyment of life remains as evident as his recall, and he tells stories charmingly. This jesting reminiscence complements better-known accounts of the genesis of "Amahl and the Night Visitors," the most popular not only of his operas but probably of all operas. As he told the tale in an essay for the original-cast recording on RCA Victor, he had accepted a commission to write a Christmas opera for the National Broadcasting Company. By November, he was still at a loss for a subject.

"I offered to give back the money," Mr. Menotti says now. "It wasn't very much. A thousand dollars, I think." NBC turned him down.

But back to the official record. Strolling "gloomily" through the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the tardy composer chanced on the "Adoration of the Magi," then (but no longer) attributed to Hieronymus Bosch. The Magi, or Three Kings, Italy's answer to our Santa Claus, were to be his Night Visitors.

The boy Gian Carlo had never actually encountered the Three Kings, the grown-up Mr. Menotti confessed in the essay: "We would always fall asleep just before they arrived. But I do remember hearing them. I remember the weird cadence of their song in the dark distance; I remember the brittle sound of the camels' hooves crushing the frozen snow, and I remember the mysterious tinkling of their silver bridles."

Who could fail to hear those memories playing through the score? Now we can account as well for the crippled Amahl and his miraculous cure. How the opera could have been created and produced in less than two months is another question. Fortunately, Mr. Menotti had a little help. "The music was all sketched out, but I was late with the orchestration," he reveals. "Samuel Barber said, 'For God's sake, let me help.' So the last page of the manuscript was written in his hand."

"I've lost the manuscript," Mr. Menotti continues. "What a shame!" It went on the block at Parke-Bernet in an auction to raise money for the Festival of Two Worlds, which Mr. Menotti founded in the Italian hill town of Spoleto in 1958. Rebekah Harkness, an heiress and patron of the arts, was the successful bidder. Shortly before she died, Mr. Menotti called to ask whether he could have it or buy it back. " 'Yes,' she said, 'but I have to find it,' " he recalls. "Then she died, and it was never found. Heaven knows who stole it."

Lost, too, is the only kinescope of the opera's premiere, on Dec. 24, 1951. Robert W. Sarnoff, the chairman of NBC's parent corporation, RCA, was showing it to someone in his office, Mr. Menotti says, and inadvertently erased it: a technologically suspect explanation for a result apparently not in dispute. Never mind. The occasion lives in history on many counts.

"It was the first color program ever on TV," Mr. Menotti notes, not bragging but indulging the curiosity of a new acquaintance who (like the opera's young protagonist) refuses to stop asking questions. "It was the first opera written for TV. It was reviewed on the first page of The New York Times. It was the first program on the Hallmark Hall of Fame. It was presented by Sarah Churchill, daughter of Sir Winston."

Mr. Menotti was 40 at the time. The television director Kirk Browning, whose name is now synonymous with the long-running PBS series "Live From Lincoln Center," was standing behind the cameras. Carmen de Lavallade and the choreographic luminaries-to-be John Butler, Paul Taylor and Glen Tetley danced the sprightly pas de quatre in honor of the Three Kings. Thomas Schippers conducted. Although no audience was present in the studio, Arturo Toscanini, that most irascible of maestros, had looked in on rehearsals and been moved to tears. But who could have predicted the phenomenon Mr. Menotti's musical Christmas card to America would become?

Mr. Menotti was 40 at the time. The television director Kirk Browning, whose name is now synonymous with the long-running PBS series "Live From Lincoln Center," was standing behind the cameras. Carmen de Lavallade and the choreographic luminaries-to-be John Butler, Paul Taylor and Glen Tetley danced the sprightly pas de quatre in honor of the Three Kings. Thomas Schippers conducted. Although no audience was present in the studio, Arturo Toscanini, that most irascible of maestros, had looked in on rehearsals and been moved to tears. But who could have predicted the phenomenon Mr. Menotti's musical Christmas card to America would become?

These days, G. Schirmer, the composer's publisher, accounts a holiday-season tally of 500 performances merely business as usual. Mr. Menotti estimates that "Amahl" has been heard in more than 40 languages, including Chinese, Dutch and Portuguese, as far afield as India, Japan and Australia. Caroline Kennedy sang one of the kings -- Melchior or Balthasar, Mr. Menotti recalls -- at school in an all-girl cast. The composer attended with her mother.

Is "Amahl" the creator's favorite among his creations?

" 'The Saint of Bleecker Street' is my favorite," Mr. Menotti replies. "I have great affection for 'Amahl' but also many sad memories. The first Amahl, Chet Allen, became so much Amahl that he could never return to real life. He became obsessed. He was in Life magazine, in Time. He was called to Hollywood to make a film, and he didn't want to do it. He only wanted to be Amahl. His parents called me in Paris. 'Please, convince him to do the film,' they begged me. 'We're poor. We need the money.' I spoke to him. It was a mistake. I told him, 'You have to think of your family.'

"So he went. It was a role for a boy soprano, but in the middle of the filming, he lost his voice. It changed. It was a terrible shock. He went home to Ohio and got very fat. He went to a psychologist. I called him to Spoleto and gave him the role of Toby in 'The Medium.' I tried to help. He was all right in the role, but he only wanted to be Amahl and never wanted to go home. In his 20's, he got married and had a daughter. Then he committed suicide. He had a very silly mother. She loved to be the center of everything. I don't think she loved her son very much. That's one reason I don't love the opera so much."

APART from these associations, Mr. Menotti feels that "Amahl," as the first of his six children's operas, is the least successful in reaching children.

"The other five, children really enjoy," he says. "In 'Amahl,' they get bored. They don't like the Mother's aria. They don't like the quartet, because they don't like people singing at the same time. They want to understand the words. Through 'Amahl,' I learned to write an opera for children. At the premieres, I always watch the audience. If a child asks to go to the bathroom, I know I've failed. With the other five operas, they never do. But with 'Amahl,' which is musically more complicated, there's always someone.

"Still, I love 'Amahl' very much, because so many people say to me, 'I came to love opera through "Amahl." ' Men with beards and four children come to me and say, 'I sang Amahl.' " How often could Mozart, Verdi or Puccini have experienced the like? Any day now, some of those men with beards will be coaching their grandsons in the part.

*

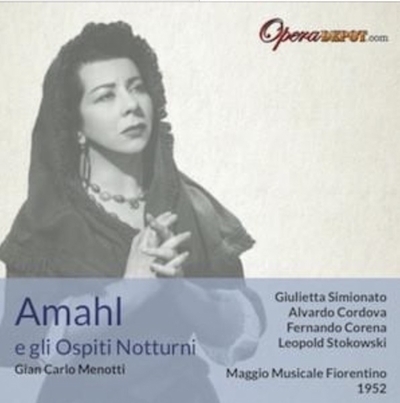

3. The Italians lay claim to Amahl, Florence 1952 (Opera Depot, May 23, 2017)

This Italian-language recording is a revelation on two counts: Giulietta Simionato gives a glorious performance as Amahl's Mother, and the orchestra, under Leopold Stokowski, shows Menotti for the imaginative master he was. It's a shame that the score—heard here shortly after the live world premiere, in English, on American television--is so ruthlessly cut. No quartet for the Mother and the Three Kings, arguably the very heart of the opera, contrasting the child sought by the kings and the child she cherishes. Also missing: the entire scene with the shepherds. Honestly, what does survive is well worth 5 stars—and the bonus tracks of Simionato in often unexpected repertoire (Mozart!) are ravishing.

This Italian-language recording is a revelation on two counts: Giulietta Simionato gives a glorious performance as Amahl's Mother, and the orchestra, under Leopold Stokowski, shows Menotti for the imaginative master he was. It's a shame that the score—heard here shortly after the live world premiere, in English, on American television--is so ruthlessly cut. No quartet for the Mother and the Three Kings, arguably the very heart of the opera, contrasting the child sought by the kings and the child she cherishes. Also missing: the entire scene with the shepherds. Honestly, what does survive is well worth 5 stars—and the bonus tracks of Simionato in often unexpected repertoire (Mozart!) are ravishing.

*

4. "The world-premiere telecast of Gian Carlo Menotti's evergreen Christmas opera Amahl and the Night Visitors resurfaces" (Air Mail, December 16, 2021)

Amahl and the Night Visitors, words and music by Gian Carlo Menotti, is the children's opera that went viral, and not only with children.

Returning in 1956 for a sixth consecutive Yuletide season on NBC, Amahl and the Night Visitors aired on "Robert Montgomery Presents"—a dramatic series otherwise devoted to nonmusical fare. The Kings, from left: Andrew McKinley as Kaspar, Leon Lishner as Balthazar, and David Aiken as Melchior. The elfin John Kirk Jordan sang Amahl in his only known screen appearance. |

In America, live telecasts (no reruns!) remained a Yuletide fixture well into the 1960s. Over the same period, the BBC and its Australian counterpart, the ABC, mounted versions of their own. Yet Menotti declared from the outset that the work had always been intended for the stage. "On television, you're lucky if they ever repeat anything," he reasoned. "Writing an opera is a big effort and to give it away for one performance is stupid." The theatrical premiere took place within two months of the original broadcast. Even Menotti's publisher G. Schirmer would be hard pressed to tally all the professional and community revivals over the intervening decades.

Surf YouTube for a few minutes, and you'll begin to sense the scope of the phenomenon. There's polyglot video—often full-length, sometimes clips—from opera houses, schools, and church basements in the Ozarks, French Canada, Argentina, Cyprus, India, China, and New Zealand, to single out just a handful of the countless pins on the map. There's an animated version, and one that casts king-size puppets as the Magi (pun intended).

A pandemic special features socially distanced singers in masks. From heaven knows where, a budding Chloé Zhao introduces her "unauthorized" home movie, mimed by her assembled teddy bears, with voiceover by off-camera family members gathered around the piano. "No bears," the tiny auteur earnestly assures us, "were harmed in this production." And let's not forget the floor show for the flock lunching at the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen on Ninth Avenue in Manhattan.

Many canonical TV broadcasts may be found as well—even the Holy Grail I never expected to find anywhere: a "kinescope" (filmed directly from a TV monitor) of the world premiere. In 1999, Menotti himself told me as established fact that the only extant copy had vanished years before without a trace. Yet here it is, in historic black and white and dated sound, glistening under its patina like a fresh-struck medal. As Amahl's mother, Rosemary Kuhlmann never externalizes, letting love and hurt and care well up from deep within. As Amahl, bereft of his flock, with nothing left to his name but his crutch and the pipe he plays on, the boy soprano Chet Allen sets the bar for all time with his good cheer, curiosity, and unspoiled sense of wonder.

And as emcee, there's the inimitable Menotti himself. "I do hope you haven't sent your children to bed," he begins, "because actually, this is an opera for children, and I don't want you to be like those awful parents who insist on playing with their children's toys."

The premiere telecast of Amahl and the Night Visitors streams on YouTube

*

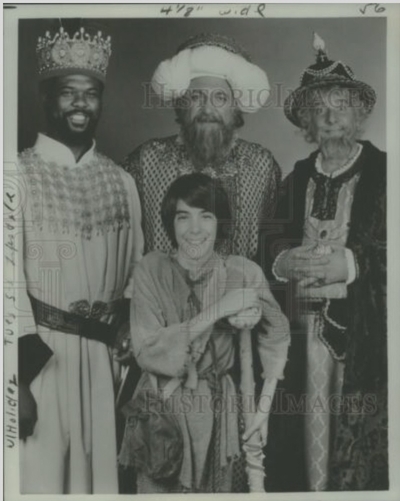

5. Moonlighting: Stars of the Met in a Holy Land Amahl - the telecast of 1978

As you may recall from the New York Times article above, Menotti's favorite among his two-dozen odd operas (several of which had extended runs on Broadway) was The Saint of Bleecker Street. Of the others, The Consul and The Medium continue to see frequent revivals. The Metropolitan Opera bypassed all these in favor of the slighter and/or lesser Amelia Goes to the Ball, The Island God (world premiere), The Last Savage, and The Telephone. The casts boasted box-office names like Roberta Peters, George London, Nicolai Gedda, Leonard Warren, and Astrid Varnay.

But why, one wonders, has the Met never touched Amahl? Family-friendly Christmas fare has been a fixture there forever, whether in the long-traditional form of the full-length Hänsel und Gretel or in the current freeze-dried one-act reductions of The Magic Flute, Barber of Seville, and the Massenet Cinderella, which are budgeted for 90 minutes but invariably run long (and feel long). Whereas Amahl was written under the constraints of prime-time television. Including credits and introductions, it could not exceed one commercial-free hour.

Top, from left: Williard White, Balthazar; Giorgio Tozzi, Melchior; Nico Castel, Kaspar. Center: Robert Sapolsky, Amahl. |

But surely Master Sapolsky's most memorable creation was the traumatized little prince Yniold in Pelléas et Mélisande (Stratas, herself a former Yniold, sang Mélisande, his stepmother). Amazing to say, he shared the role with a classmate: Adam Guettel, son of Mary (Once Upon a Mattress) Rodgers, grandson of Richard (Oklahoma! etc.) Rodgers, and future Tony Award-winning composer in his own right for A Light In the Piazza. As Yniold, these two etched themselves deeper into memory than anyone else I have ever seen in the part. While those assignments seem to have gone undocumented, the Sapolsky Amahl lives on YouTube. Some will say his beautifully voiced and stylishly acted portrayal is too stage-wise for the camera, and that may be true. Yet I like to imagine how he would have projected at the Met--and hope that future generations of young singers will get their shot.

*

6. Balthazar, the Black king

Cancel! Sir Laurence Olivier's Othello (1965), with Frank Finlay as Iago. |

That's how it is in the Adoration of the Magi said to have inspired Menotti, not to mention countless other Old Masters on the same theme. And in the opera, it's spelled out as it were in capital letters that what astonishes Amahl most of all about the Night Visitors is the color of Balthazar's skin.

In the premiere telecast of 1951, Leon Lishner sang Balthazar in blackface. Returning to the role in 1956, he showed the complexion he was born with.

Remarkable, no? To the best of my knowledge, the culture wars over "exotic" or race-nonconforming stage makeup were not to flare up for decades. The film of 1978, directed by Arvin Brown, quietly marks a progressive milestone, too: in that version, the part of Balthazar is taken by the regal Willard White, a Black bass-baritone from Jamaica (see photo above). I can't tell you whether he was the first, but I do know there have been many more.

*

7. Amahl and the Night Visitors at the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen (Air Mail, November 18, 2022)